If you have no choice, is it courage?

On Chocorua, Chapter 6

Imagine a time before cell phones, before waterproof Gore-tex, a time when college campuses were not the near-Michelin star establishments many of them are today. This is when my story takes place. It’s too long for one post, so I’ve broken it into six installments, or chapters. That’s the logistics.

But here’s the kicker: Other than Jake Hoffman’s name, it’s real.

It happened.

To me.

Read/listen to previous chapters.

Chapter 1: How I nearly killed my feet.

Chapter 2: We should have turned back. We didn’t.

Chapter 3: We reached the summit. Too soon.

Chapter 4: “Shivering” takes on a whole new meaning.

Chapter 5: Sometimes I know better than an “expert.”

The terrain was not familiar; we were not on a trail that I could see, and there were no footprints in the snow from our journey up yesterday, but I knew—I knew—that I was going in the right direction.

Before long we found ourselves crossing a large open area. Perhaps it was an alpine meadow? But no; once we were well into it, all evidence pointed toward its having been a small section of woods, mostly of young trees and saplings, that must have burned. The trees had fallen onto bare ground, last fall or five years ago—who could tell—and they lay unpredictably crisscrossed, hidden by a couple of feet of snow.

Even if my brain had been functioning at peak efficiency, I couldn’t have counted how many times a step would land one of my feet deep in the snow, boot held annoyingly between two hidden branches, or a trunk and a branch, or whatever the hell was down there. More than once I had to take off my pack, then find leverage somehow to pull my foot up and out of the boot—which couldn’t be fastened very well onto the swollen foot—and then fish around under the snow to extricate the boot. And then, of course, I had to put the boot back on, still too small to accommodate the foot, still with my heel riding half an inch above the boot’s footbed. Jake’s gaiters would have been more helpful if my boots hadn’t kept coming off. And in fact, they were more hindrance than help. I took them off and handed them back to him.

Jake was having similar problems, though I don’t recall that either of his boots ever came off. But he had serious boots, boots that fit. At one point I sat still on the snow, waiting for the energy to fish for a boot the dead trees had captured, and I watched Jake. He had reverted to the technique of being angry at the mountain and, I hoped, angry at himself, and he was using that anger to help himself keep going. I already knew that approach wouldn’t work for me, so I just reached for the boot, knocked as much snow out of it as I could, put it back on as well as I could, struggled to my feet, shrugged back into the pack, and kept going. There was no other option.

By the time we made it to the other side of that hell-hole of a clearing, Jake had resumed his lead position.

“Did you see a trail marker?” I asked, hoping against hope.

“No. But I realized you’re right about our direction.”

I guessed I wasn’t going to get an actual apology. Not about leading us in the wrong direction. Not about his ignorance of the trail system. Not about the madness of climbing in yesterday’s weather. Not about his lack of advice on clothing and boots and gaiters. Not about nearly getting me killed. Not about anything.

I kept expecting we’d run into the Piper, and so did Jake, but he had decided the cabin must be nearly on the opposite side of the mountain from that trail, and we’d just have to keep going.

We’d crossed a couple of small streams on the way up, I vaguely remembered, so we were not expecting to come across a deep ravine with running water rushing downhill. I say deep; it was perhaps fifteen feet down to where the icy water bounced raucously over boulders and bits of fallen tree.

We stood there staring into the depths until Jake looked downstream. “Maybe there’s another way across.”

A way other than climbing down into the ravine, if we could even do that, and praying we could make it through the water, was what I knew he meant. I looked upstream.

“There.” I pointed with a finger in the toe of my grey tweed sock at a white pine that had fallen across the ravine.

We trudged uphill to the tree, a new puzzle to stare blankly at. The tree was thick and would no doubt be strong enough to support our weight, but the trunk was riddled with branches, big ones and little ones and tiny bumps that stuck up from the trunk just enough to trip us and send us tumbling into the ravine.

I heard Jake say, “We have no choice.”

Silently I turned and climbed onto the tree, painfully aware that my sleeping bag was woefully unbalanced and was not going to be my friend during this crossing. It had been frozen into the shape of our makeshift roof overnight, and although Jake and I had done what we could to scrunch it enough to fasten it into place on my pack, it was hardly in an efficient roll.

We have no choice.

The rough bark of the white pine was coated here and there with a layer of ice. I reached for the first branch high enough to be helpful to me, and as I inched past it the sock on my hand caught on it, and my hand came loose from the sock suddenly. I nearly fell.

“Don’t stop! I’ll grab the sock. If you can take the other one off, you should do that.”

Hanging onto one branch and then another, shifting my ill-shod feet on the slippery trunk, I managed to pull the other sock off with my teeth. It hung from my mouth as I continued across.

You always hear, “Don’t look down.” I didn’t. But I didn’t need to; I’d already seen what it looked like down there. All my attention was on placing my boots around branches and not on little stubby bits where branches had broken off, finding hand-holds on the irregularly placed branches within reach, shifting weight gingerly to be sure the foot ahead of me wouldn’t slide off the tree, and looking ahead to plan the next step.

Against all odds, I made it across and climbed shakily off the tree and onto snow-covered ground, Jake behind me. He handed me my other sock, and as I put both socks back onto my hands, I realized my hands were painfully cold again. I tried gripping one fist inside the other hand, but that didn’t help. I started to rub the back of one hand with the other, but Jake stopped me.

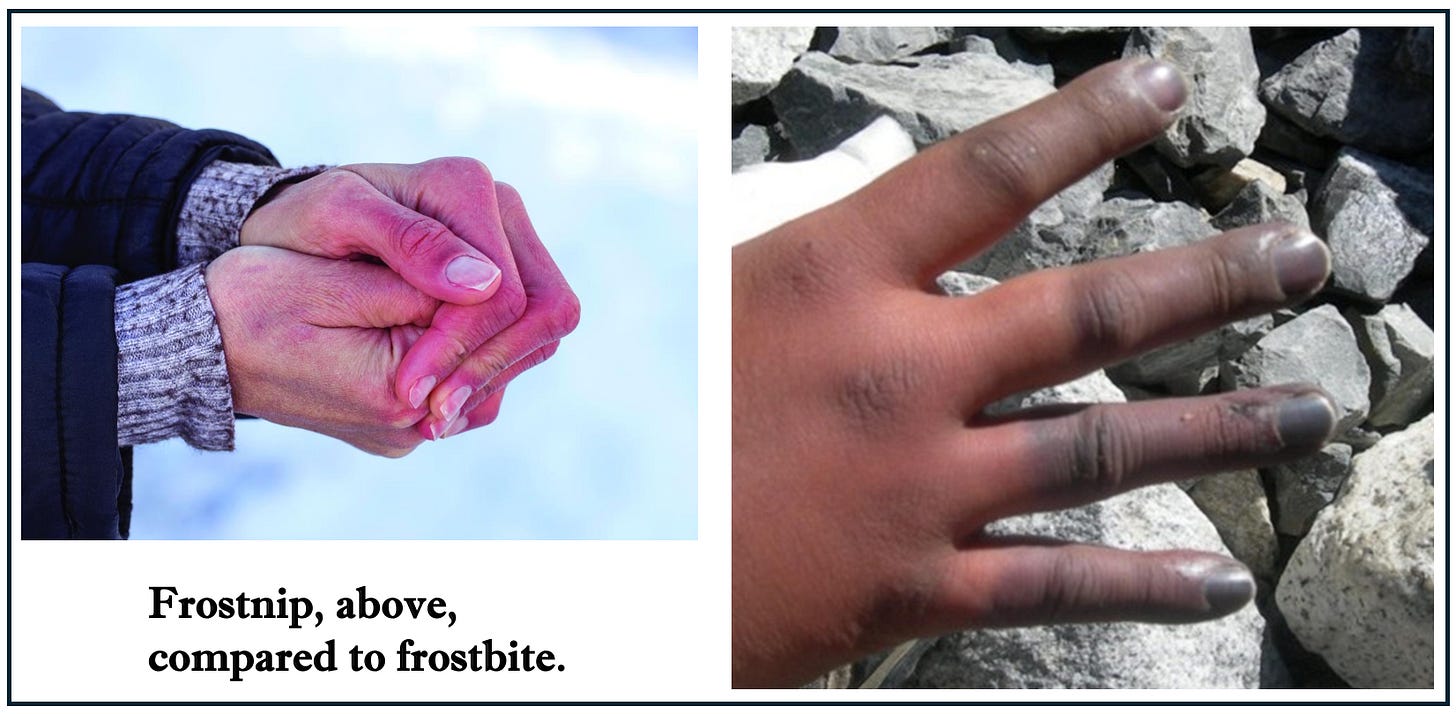

“If there’s frostbite coming on, you shouldn’t rub the skin. Take the socks off for a minute.”

I stared at him; he must be crazy. He removed the socks from my hands. Unzipping his jacket, he lifted his clothing and pulled me close to him, leading my hands into positions against the bare skin under his arms. He gasped as my cold flesh touched his warmth.

We didn’t actually hug, but we were close enough to lean our foreheads together, so we did that. I looked down at our respective boots, taken aback yet again at the difference between his pair and mine. I closed my eyes.

And then it came.

“Short mort, I am so sorry. I'm so sorry I got us into this. I have made so many mistakes. If you had more experience, I know you would have stopped me at several points. But you couldn’t know.”

I could have said, That’s all right. I could have said, I should have stopped you anyway. I could have said any number of things to make him feel better. But what I wanted to do was list all the other things he should be sorry for. This was supposed to have been my fun introduction to hiking. Instead I’d nearly frozen to death, and now I had frostbite, the effects of which would last the rest of my life. So I said nothing.

It was nearly dark when we found the Piper Trail. And we came to the parking lot not long after that. So we’d bushwhacked most of the way down Chocorua. In the winter. Hungry. Frostbitten. Exhausted. And yet the sight of his Jeep made us both yell with delight.

We threw our packs into the back seat. Jake turned the engine on. As soon as there was enough engine warmth to run the heater he turned the temperature and the fan to high, and we huddled as close to the vents as we could get, teeth chattering, for maybe ten minutes.

Gradually, Jake relaxed back into the driver’s seat, and even more gradually, I sat back as well. I still couldn’t feel my feet; I wasn’t sure what I was going to have to do for them.

I looked at Jake. “Onward?”

“Onward.” He threw the car into gear.

I don’t remember the trip back to campus, other than a stop we made, I think in Ossipee, at a fast-food place. By that time, my feet felt like they were in a slow burn.

Getting out of the car was ridiculous. We were both so stiff, and had so little energy, that we couldn’t straighten up. We hobbled like mountain trolls across the parking area, just managing to straighten up before going into the restaurant.

There weren’t many people in the place, but by the time Jake and I stood at the order counter, all eyes were on us. It wasn’t until we sat down with our food, across a booth table from each other, that I figured out what had attracted so much attention.

Despite how starving I was, one look at Jake, fully exposed to indoor lighting, and I laughed. And laughed. He looked puzzled, although he shouldn’t have been, because I must have looked just as absurd.

His navy wool hat was stuck full of forest detritus. Bits of twigs, fragments of dried leaves, the occasional spear of a brown evergreen needle had all taken up residence on Jake’s hat and, I was sure, on my own. If that wasn’t enough, where his turtleneck showed above his jacket was similarly decorated.

I pointed at his hat, then at mine, and managed to say, “I think we’re scaring people.”

We practically inhaled burgers, fries, and hot coffee each, barely rejected the idea of more, and got up. Or tried to get up. We did, of course, but sitting had made us stiff again, and getting out of that booth was harder than climbing out of the car had been.

The rest of the ride back to campus did not register in my brain.

As I’d predicted, my feet would never be the same. The swelling was so bad I couldn’t see my ankle bones, and I had doctor’s orders to stay off my feet for two weeks. Jake visited me once as I lay half-prone on my dormroom bed. He apologized again. And then he said something I’ve never forgotten.

“I think you are the strongest woman I have ever known. Maybe the strongest I will ever know.”

I think it was about a week later that the nail on my right little toe fell off. It grew back, and then the next March, on the anniversary of the hike, it fell off again. It fell off and grew back maybe twice more at irregular intervals before staying put. But years later, that toe—which kept growing bone spurs to protect itself—had to be amputated.

My mistreated feet still suffer. One podiatrist said the frostbite had broken their thermometers, and they were unable to regulate themselves. He was right; for in summer, when they get painfully hot, they don’t know any better what to do about that than when they get painfully cold in the fall, winter, and spring. I’ve had to develop techniques to help them through all weathers.

That summer, I hiked Chocorua’s Piper Trail again, with friends. A few years later, I hiked the mountain alone, on the Champney Falls trail, and then again one autumn, when I led a photo group to the summit. And I’ve hiked many mountains since, throughout New England and in Europe, sometimes alone and sometimes not. But never in winter. Never again in winter.

Was there a lesson I took from this misadventure? More than one, I think. First, Jake was right. I am strong. Not just in body, but also in spirit. I learned that anger is not my friend, and that my brain is just as important as my body. I learned that courage doesn’t mean being without fear. It means going forward even when you are afraid. And for me, fear comes ahead of doing something; while I’m pushing forward through adversity, I know how to set fear aside. So I don’t think of myself as courageous. But I do think of myself as powerful.

I don’t know where Jake is today. I don’t feel as though I owe him anything. But I owe an awful lot to Chocorua.

You can subscribe for free to Robin Reardon Writes, though I hope you’ll consider becoming a paid subscriber. It’s not expensive, really! You’ll have access to everything I write on Substack. You’ll also have my undying gratitude.

One more thing: If you share this post, you’ll get credit for generosity, and I might get more subscribers.

I’m an inveterate observer of human nature, writing stories about understanding and connecting with each other. My primary goal is furthering acceptance of people who appear to be different from “us,” whoever that “us” might be. Check out my books on my website.