Altruism: Is it a thing?

I think not.

Free Fall

The speed at which an object falls will increase, during that fall, due to gravity. According to a theory put forward by Galileo Galilei, the gravitational acceleration would be the same for all objects. But that theory is not something we can prove in reality, because a falling object is subject to the effects of factors other than gravity.

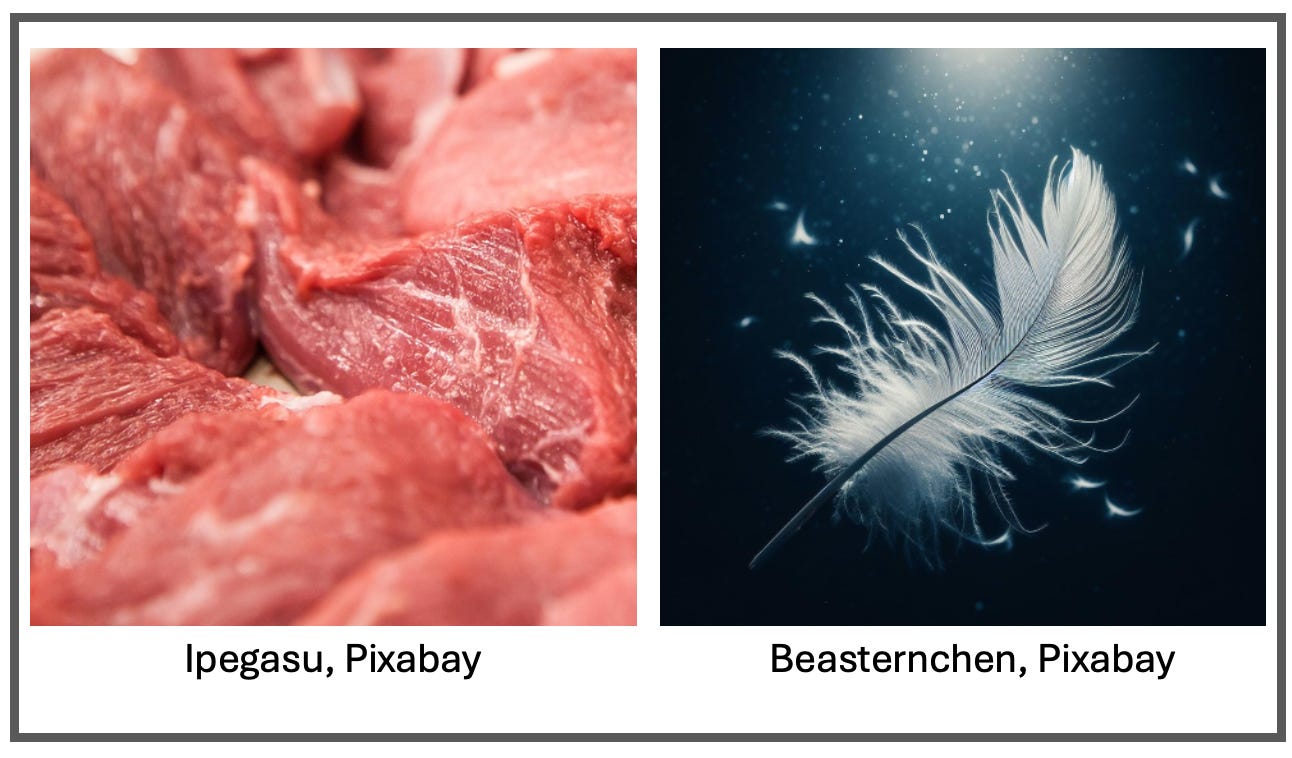

For example, let’s say Galileo has a canvas bag full of feathers. The net weight of the feathers is one pound. He also has a bag containing a pound of pork meat. Obviously, the pound of pork meat weighs no more than the pound of feathers.

If Galileo and a friend were to climb up the tower of Pisa, each holding one of these two containers, lean over the top edge, and release the contents of their one-pound bags at the same moment, the feathers don’t stand a chance. Sure, the surface of the pork would meet with atmospheric resistance that would slow it down. However, the tiniest updraft (or, really, a draft of any kind) would send each feather off course, and it would take quite a while for all the feathers to stop falling. Some might travel quite a distance before settling.

It's evident, then, that as far as humanity can tell, there is no natural environment on Earth where the free-fall formula of 32 feet per second/per second can be demonstrated. It exists in theory, not in reality.

Altruism: Giving with no expected return

The range of definitions, explanations, and examples I found in a general search for “altruism” was baffling. There are even sources attempting to segment it into categories, depending on who benefits from an altruistic act. But can there be, in reality, such a thing as pure altruism?

One area of examination might be charity. Let’s say you love pandas, and you decide to give $100 to an environmental group benefiting those adorable, silly creatures. The benefit to the organization is tangible (or it can be applied in tangible ways). The benefit to you is—what? Is it nothing? I don’t think so. Your benefit might not be tangible, but it is real. It’s a surge of warm feeling that you’ve done something good for a cause you care about.

Another place we might be tempted to see altruism is in the life of Mother Teresa. She dedicated herself to the service of others. This dedication was, originally, directly aligned with her faith in God, but even after that faith faltered she kept up her dedication to other people. Was this altruism?

What would have happened, I wonder, if someone had plucked Mother Teresa from her challenging existence and set her down in a comfortable home with all the amenities most of us want? It seems to me she would have lost her mind. She needed to do what she was doing. I can’t say where that need came from, but I don’t doubt that it was real. And she needed to fill it. This is not altruism.

And speaking of God....

The story of the Good Samaritan is often given as an altruistic example. A Jewish man had been beaten and left to die. Two Jews passed him by, probably because of Torah-related laws about purity pertaining to their religions roles. Then a non-Jew, a Samaritan, stopped and cared for the beaten man. It seems reasonable to believe the Samaritan expected no reward for this, especially given the animosity between the Jewish establishmen and Samaria. So did that lack of expected reward constitute altruism? We don’t know. We don’t know how badly the Samaritan would have felt—how haunted he would have been—if he had left that Jew to die.

In Matthew 19:21 Jesus tells a wealthy man that in order to receive treasure in heaven, the man must sell all that he has and give the proceeds to the poor.

This verse has always bothered me.

If George sells his possessions, they pass from him, but they land on men like Bob, who purchases them. Wouldn’t that mean that Bob is now handicapped with George’s possessions which, added to his own, would put him that much further from heaven’s treasures?

Why wouldn’t George just give his possessions away to people who need them? Why bother to sell them? Maybe the very process of selling his goods, which takes longer than just donating them, is a kind of test: Can he go through with this? If so, it’s hard to say what the benefit is, or to whom.

Jesus says nothing about heaven’s treasures being awarded as soon as the possessions are gone. If George is left alive on Earth with nothing, however that came to be, isn’t he now one of the poor? Mustn’t he now beg from others to reacquire at least some of what he sold?

Also, this verse sets up a chain reaction. George sells his possessions to Bob, who needs to sell all he now owns to other wealthy men who must, in turn, sell theirs, who must in turn sell theirs, who must in turn.... This is beginning to look like every man for himself. And every man is promised treasures in heaven.

If nothing else is clear, it’s that following this advice from Jesus doesn’t fall into the category of altruism. Treasures in heaven, indeed.

Giving as a personal shield

Let’s say Myra gives money every month to a cause she doesn’t care about, but it’s one that was very important to her late mother. Does she get a warm, fuzzy feeling every time she gets an acknowledgement for that charity? Maybe, maybe not. Is it altruism? I don’t think so; sometimes altruism isn’t so much what you get in return as it’s what you don’t get. Like the Samaritan, Myra would no doubt feel guilty if she didn’t make those contributions, and she wants to avoid that feeling.

On the other hand…

I absolutely adore snow leopards, and I give on a monthly basis to the Snow Leopard Trust. I want to do my part to help make sure these magnificent, endangered animals are protected. The Trust rewards me by sending emails asking for yet more money. I don’t mind, because these messages include photographs of their efforts to protect the wild leopards in the Himalayan Mountains. Each month, I receive an email acknowledgement for my contribution, and each time I see one I get a soft, warm feeling.

Make no mistake. This is not altruism.

The best return on investment

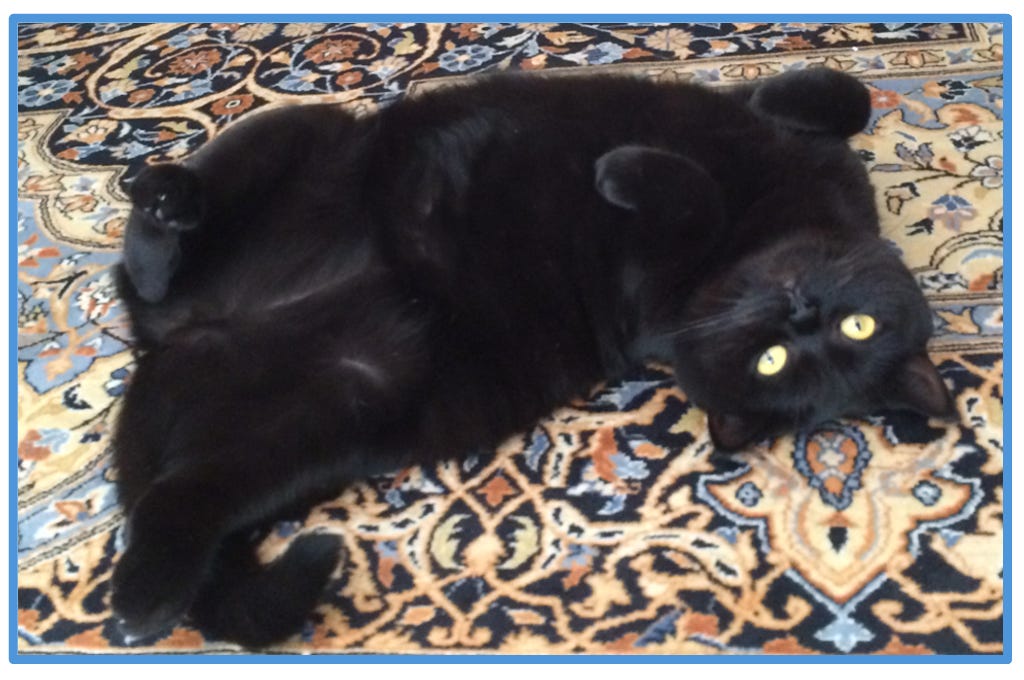

Recently someone I know—we’ll call her Amanda—asked me why I like cats. “They’re aloof creatures with no loyalty,” she said. “They don’t obey commands. They don’t do anything for the good of anyone else.”

Clearly, Amanda has a blind spot and knows nothing about cats.

It’s true that cats are the opposite of altruistic. Sure, there are cats who’ve been known to do things like alert its people of a fire in the house, even when the cat could have escaped on its own. And there are cats who will follow simple instructions. But by and large, cats let you know what they want. If they get it, they don’t thank you. A cat might seek out your warm lap; if so it will be in part because they have formed a bond with you as a central aspect of their environment, and in part because they seek warm places.

“Surely you don’t think your cat loves you, do you?” Amanda asked.

“Yes, and no,” I said. “My cat considers me part of her world, so she misses me when I’m not there. She looks to me for food, for comfort, for stability. But here’s the best part.”

I waited until I was sure I had Amanda’s attention before I added, “My cat allows me to love her however I need to. I show her that love by meeting her needs. And in return I get the best reward of all. Joy.”

Amanda is taken aback. “Joy?”

“It’s wonderful to be loved. But the true source of joy is in loving.”

And even that is not altruism.

You can subscribe for free to Robin Reardon Writes, though I hope you’ll consider becoming a paid subscriber. It’s not expensive, really! You’ll have access to everything I write on Substack. You’ll also have my undying gratitude.

One more thing: If you share this post, you’ll get credit for generosity, and I might get more subscribers.

I’m an inveterate observer of human nature, writing stories about understanding and connecting with each other. My primary goal is furthering acceptance of people who appear to be different from “us,” whoever that “us” might be. Check out my books on my website.

I had an enormous black cat we named Bandit when we rescued him. He had one small spot of white on his chest. He was a very chill cat, but shortly after we got him he got the zoomies and ran up my husband’s arm and through a picture window opening in wall. The person who gave him to me said, “Oh, yeah. That might have been because the couple who had him were getting a divorce and the man wasn’t very nice.”

He turned out to be quite a sweetheart, even if he was aloof much of the time. He wasn’t a lap cat, except while I was pregnant. After our son was born, he wanted to sleep in the crib with him, which naturally scared me. He seemed to have this bond with our newborn. He would often climb onto the bed with our son when he was a toddler and into his early teens.

It was so sad when he passed, but we’d had the joy of his company for 15 years. We still miss that big boi.

It may not exist, but it's something to strive for, I believe.