A Dangerous Paradise

The Kalalau Trail, Part 1

“Come experience a place where the physical and the spiritual are one. A place where magic happens, where the very names are magical: Na Pali. Ho’olulu. Waiahuakua. Hanakoa. Hanakāpīʻai. Come to Kaua’i.”

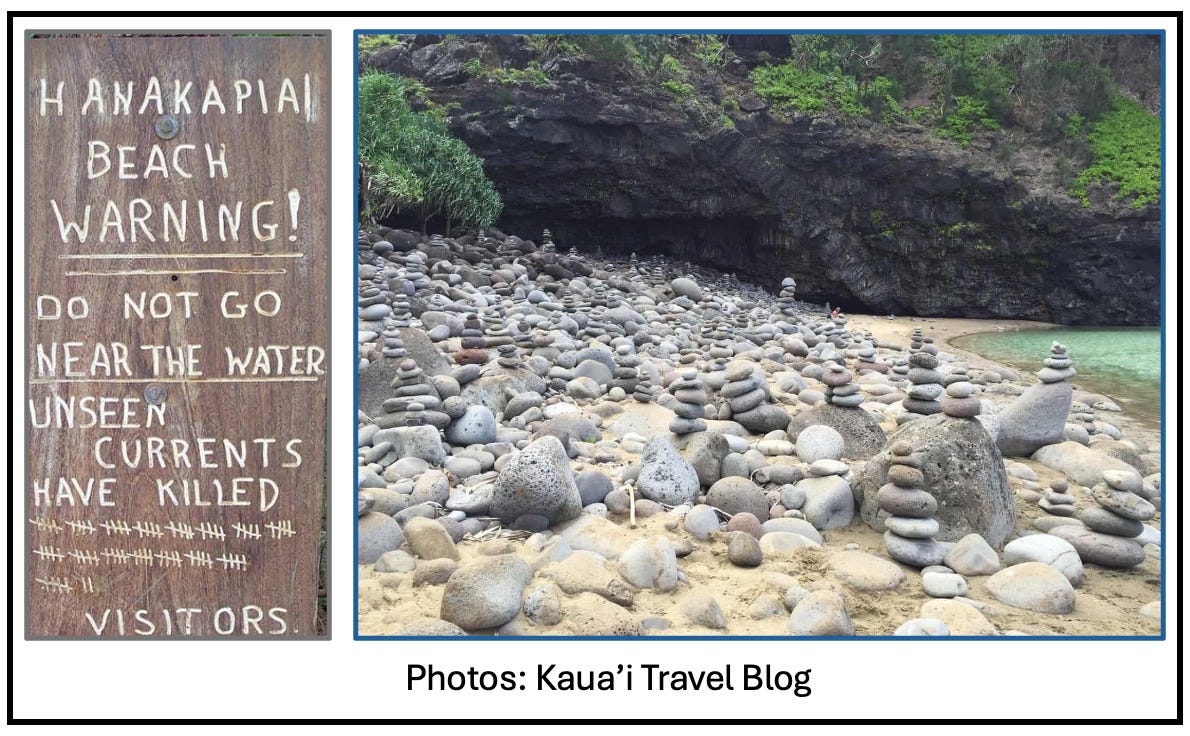

Na Pali, the northwest coast of the island of Kaua’i, really looks like the photo above. I’ve been there. I hiked only a couple of miles down the 11-mile Kalalau Trail, as far as the deceptively charming Hanakapi’i Beach. There, many waders have been claimed by the ocean, dragged down and out by a secretive, inescapable undertow.

This is the first of two parts of a story, excerpted and adapted from my novel, On The Kalalau Trail. I apologize in advance for this post ending in a cliff-hanger. Literally.

Conroy Finnegan had warned me. In fact, he’d shown me. As the sole proprietor of his hiking tour company, Finnegan’s Walks, he had once led a trip to the north shore of the island of Kaua’i, following the Kalalau Trail south from Ke’e Beach. What he warned me was that it was treacherous. And he was going there again. And he wanted me to sign up for the trip.

I’d become enthralled by Conroy so quickly it had made me dizzy. A newly-minted college grad, I’d had just enough experience as a man attracted to men to know that he was a rolling stone, sending down roots nowhere. I had not quite enough experience to realize that I cared more about him than he would ever care about me. It hadn’t helped that his physical prowess transferred easily and enthrallingly from the hiking trail to the bedroom.

I’d gone to his apartment that evening hoping for a little more than a tour of his trips, but first he wanted me to see the Kalalau. Obediently, I sat facing his computer and watched. Although I ooo-ed and ohhhh-ed at the first few images on his computer screen, I was not feigning enthusiasm; the scenes were beyond glorious.

And then came an image of turquoise water hundreds of very steep feet down on the right, a rim of white lace where sparkling water met red-brown rock. Directly in front of the camera was the fully-loaded frame pack on the back of a hiker. He was slightly bent to his left, a hand held out to steady himself against the nearly vertical rock face beside him, his head down to watch his feet as they did their best to stay on the narrow trail and avoid tumbling down to that turquoise water below. His right hand was wrapped tightly around the handle of a trekking pole, which he’d apparently stabbed into the tiny bit of level ground between his right boot and oblivion.

Conroy said, “Crawler’s Ledge. There must be a Hawaiian name for it, but I’ve never known what it is.

“Anybody ever fall?”

“No one who lived to tell about it.”

I turned in the chair to look at him. “You said this was paradise.”

“I also said it was the place where there’s no bridge between life and death, because they’re both right there.” He nodded toward the screen. “The kind of beauty that makes you glad to be alive. The kind of danger that makes you acutely aware of being alive. And the chance, almost any second, that you’ll pass into another plane of existence.”

He'd convinced me. It hadn’t taken a lot of effort. Not only was I attracted to him (although I knew that once I joined the walk, I would be just another hiker), but also I needed what he’d promised Kaua’i could offer. I’d started hiking mountains three years ago after my older brother Neil had died. He’d been hiking with a friend in extreme wilderness when they’d been overtaken by a forest fire. I had idolized Neil. He’d been the first person I’d come out to as gay, and he’d accepted me without question. After he died, I’d donned the metaphorical boots that had been burned off of my brother’s feet.

And then, a year later, the only person I’d ever known as a parent—my grandmother—had died. She had raised Neil and me since I was two years old, and I’d cherished her. And as I’d gone through her house and its contents, I found things that revealed to me a woman I’d barely known.

She’d been very active in her church, a church I thought she’d attended more by routine than by devotion. I was wrong. The degree to which she’d been involved in every aspect—from singing in the choir to managing bring-and-buy sales to organizing a charity outreach program—stunned me. Then there were the photo albums. Oh, sure, I’d seen some pics from her early years. But going through her personal treasures I found albums containing photographic evidence of a woman who’d traveled much more than I had known. A woman who’d had boyfriends before she’d married my grandfather which, though it seemed obvious, made me sit back on my heels. But had I ever considered her that way? As a real person, with a life I knew nothing about? I had not.

If that wasn’t enough, remnants of Neil’s life were also there, waiting for me to unearth them. I found letters from his girlfriend Cotton, to whom he’d been engaged when he’d died, that drew pictures in my mind of a young man who was so much more than my brother, a man who had radical ideas about forest management and who wanted to build his own cabin (though Cotton referred to it as a vacation home) and wanted to have at least four children. Had I known any of this? No. I had seen him, I realized, as part brother and part surrogate father.

Do all children fail to see their parents as people? Even surrogate parents?

Digging up one proof after another that I’d followed my own life in ignorance of theirs had left me with a profound sense of shame, a shame that cried out for atonement. Suddenly I craved connection with people I could no longer connect with—not without something magical, or spiritual.

Perhaps, I thought, that connection could happen in a place where (as Conroy had put it) life and death existed together, a place where I didn’t need a bridge to make a connection. So a few weeks later, here I was, along with several other people on a Finnegan’s Walk, following the Kalalau Trail down the Na Pali Coast.

All the hikers had gathered the night before over dinner where we were staying. The only woman was Margot Truman, a grad student in social work. One fellow, Owen Palmer, struck me as annoying at first, and then insecure despite his wealth, which he made as obvious as possible without saying the words. If we missed the conspicuous branding on his expensive hiking clothes, during our dinner conversation we would still have heard about his country club, his golfing, and the ivy-league colleges his kids were going to.

Erik Buxton, a pilot from New Zealand, seemed older than the others, maybe in his forties. His brownish hair was thinning and pulling back from his freckled forehead, and the skin around his blue eyes had the look of someone who’d spent a lot of time squinting against the sun. I enjoyed Erik’s “kiwi” colloquialisms. I mean, who knew “I’m chocka” meant that you’d had a little more than enough to eat? Or that “Sweet as” was all one need to say about something really nice? “Wop-wops” is Kiwi for the middle of nowhere. “Hard out” is the same as “for sure.”

What I liked best about Erik, though, was that he felt just as I did about Owen. He was great at feigning innocence as he said something to get a rise out of the man, like when he pretended to admire Owen’s shirt as we gathered at the trailhead in the morning.

“Nice shirt,” Erik said as he winked surreptitiously at me. “Liked it just as well last night.”

Owen’s mouth fell open, his eyes wide with indignation. “It is not! That one was a completely different color!”

“Hmmm. Guess the word ‘marmot’ printed there on the shirt fooled me. Didn’t seem like there’d be two of those.”

“Marmot? This isn’t some kind of ground hog. It’s Mammut!”

Yes. I liked Erik.

The first part of the trail was as glorious as Conroy’s photos had promised. Starting hundreds of feet below us, brilliant blue sea stretched endlessly to the right. To the left were steep slopes, though nothing like the claustrophobic terrain the Crawler’s Ledge would have. The slopes here were covered in greenery, tropical and lush. Ahead, knife-edged green fingers punctured the water at intensely awkward angles, and beyond them purple-blue knives of land plunged into the sea.

As we approached the sweet-looking little Hanakapi’i Beach, we passed several rustic signs, each warning us not to approach the water. It was tempting; standing on the sand, hundreds of stone cairns on our left and the sinister ocean on our right. The gentle waves seemed to call to us. “Take off your boots,” they said. “Refresh your tired feet in our cool caress.”

But we had been warned. The steep topography, evident above the water and plunging just as steeply into it, created an undertow so powerful that anyone caught in it would be swept quickly down and out to sea.

We’d camped for the night a little off the trail, not far from a relatively flat spot on this torturously steep part of the island. We couldn’t camp on that spot. A threatening sign said not to; it was one of the very few places flat enough for a helicopter to land in an emergency.

Several miles and a side trip inland to see a waterfall later, we were approaching the start of Crawler’s Ledge, just about to take our lives into our hands. I was walking behind Margot, who had shown herself to be quite the trooper; her pack was no lighter than anyone else’s, but she’d kept up with the best of us. In front of her was Owen, who’d been using two trekking poles despite Conroy’s advice to bring only one pole today.

Conroy, in front of the group, stopped and turned, dropping his pack with a solid thump onto the red dirt that’s ubiquitous to these islands.

“Couple of Hawaiian terms for you. Mauka is how you refer to the mountain side of a trail. Makai is the ocean side. There’s a good reason the language has terms for these relative positions, as you might have realized already. Not too much farther ahead you’ll start to see signs warning you about danger. That would be the famous Crawler’s Ledge. I know you’ve heard this before, but I’m gonna tell you again anyway. This trail is dangerous.”

He looked at each of us in turn, his face heavy with warning. “On your left, mauka, you’ll be penned in by rock. Unforgiving, straight up for many feet, rock. Only a few feet away, and sometimes less than that, is the makai. There will be nothing but empty space between you and a fall that will last only until your body smashes onto the rocks below. It might be carried out to sea, or it might lie there until it’s picked apart by sea birds, depending on the tide and just where it falls. Don’t be that dead body. I want you all going home and bragging to everyone you know about your prowess on one of the most perilous stretches you’ll ever see.”

He pulled a telescoping trekking pole out of his pack. “This ledge is when you will need the pole I told you to bring. You will want to keep it on the makai, your right, to help you balance away from the edge. Do not,” and he looked at Owen, “make the mistake of thinking you’ll have any use for another pole. There might be a few places you would have room, but it won’t help you. And the last thing you want is to push yourself away from the rock. You should be working with all your might to stay close to that rock. Got it?”

There were murmurs of assent as those of us who didn’t already have their poles out dropped our packs to retrieve them.

In less than half a mile, if I gauged correctly, we started to see the warning signs Conroy had predicted. They got more urgent as we went forward toward a cliff face that loomed ahead of us. And soon we were on it.

Conroy had not exaggerated. The trail, if it could be called that, was dizzying and spectacular. Almost every step was a challenge. There were places where I felt safer than others, but for the most part every step was an opportunity to find out what it might mean that here on Kaua’i, Paradise was double-edged. And there was no help; there were no guardrails, no hand-holds. My survival was all up to me.

It was exhilarating. I loved it.

We were maybe halfway through this death-defying portion of the Kalalau, by my reckoning anyway, when a gust of wind came whipping out of nowhere. It lifted a small canvas cover completely off of the top of Owen’s pack and sent it flying toward Margot.

Two things happened at once. First, Margot gave a little scream. And then she disappeared over the edge.

You can subscribe for free to Robin Reardon Writes, though I hope you’ll consider becoming a paid subscriber. It’s not expensive, really! You’ll have access to everything I write on Substack. You’ll also have my undying gratitude.

One more thing: If you share this post, you’ll get credit for generosity, and I might get more subscribers.

I’m an inveterate observer of human nature, writing stories about understanding and connecting with each other. My primary goal is furthering acceptance of people who appear to be different from “us,” whoever that “us” might be. Check out my books on my website.